By Marty Finley – Reporter, Louisville Business First

Jul 5, 2019

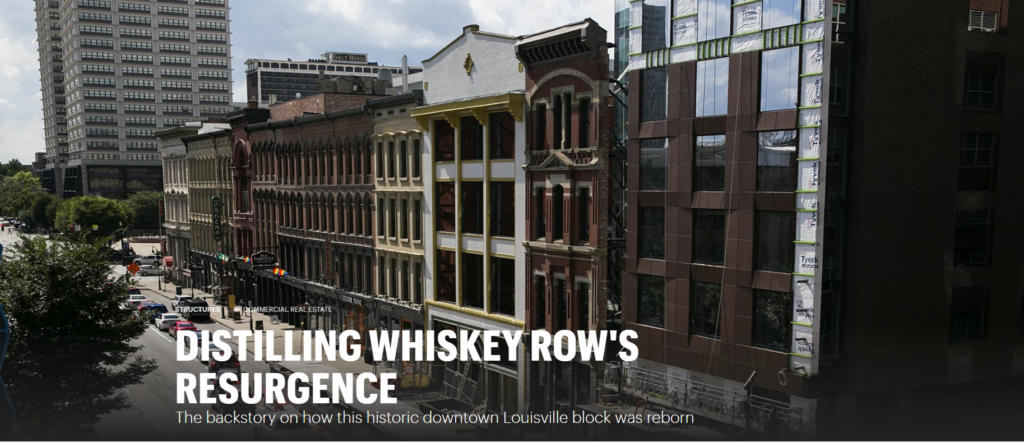

Eleven years after Julie Lavalle Jones moved back to Louisville from North Carolina to help bring her father’s vision for Whiskey Row alive, most of the work is finally nearing completion.

Jones, who goes by Valle, and her brother, Stephen, have been working for years alongside Louisville business leaders such as Bill Weyland, Todd Blue, Steve Wilson and Laura Lee Brown to resurrect the once moribund Whiskey Row block in a way that would not only return it to its bygone splendor but elevate the block to a regional tourist draw.

And the developers and tenants we spoke to said the completion of the Hotel Distil and Moxy Louisville Downtown later this year will close the loop on the redevelopment, bringing both Main and Washington streets to life as pedestrian-friendly entertainment hubs. Projects such as Old Forester Distilling Co., 111 Whiskey Row and Whiskey Row Lofts have already stimulated interest through a series of restaurants, bars, retail uses and offices.

Together, developers have invested $200 million or more into Whiskey Row during the past decade.

Paired with the site’s history dating back to Prohibition, the components all tie together to give Louisville a genuinely unique experience to share with the world.

“If you go to Nashville, you want to go to honky tonks, right? If you go to Memphis, you want to hear the blues. And if you go to Louisville, you want bourbon. And you want Whiskey Row. You want local. You want to know what’s cool here,” Jones said.

The emotional investment

For Jones, this real estate renaissance has been a personal journey. Her father, Larry Jones, first dreamed up a plan of a mixed-use Whiskey Row in 1984, with establishments where visitors and locals alike could live, work, play and stay. Larry, a local magician, operated Squirrelly’s Magic Tea Room in the former L&N building at the corner of Second and Main streets for years, after his house could no longer contain all of his magic tricks.

He paired the theater with an Italian restaurant — figuring more people would come to a magic show if they could grab dinner at the same time. That restaurant is long gone, replaced by Bearno’s By-the-Bridge in 1997.

But Larry’s ambitions extended far beyond his theater. He tried for years, with other business partners, to buy other buildings along the block, including the former Burwinkle-Hendershot Co. property next door to his building, and properties down the street that contained fully functioning businesses.

No one was interested in selling.

But he had other problems. Even if he could acquire the needed properties, the Louisville waterfront was poisonous to would-be investors because it was besieged by unattractive heavy industrial users.

“We went and met with several large urban mixed-use redevelopers,” Valle Jones recounted while sitting in a booth at the Hall on Washington, a new German beer hall in 111 Whiskey Row. “I remember going to one in Washington, D.C., and sitting in the room and bringing photographs and aerials, and all this kind of stuff. He said, ‘as long as you have that heavy industry — sand companies, junkyards and a CSX rail line with a heavily used commercial railroad — between you and the river, this block will never be developed. Even if you acquire all those buildings, this will never be developed until the city takes the negative and turns it into a positive place.’ ”

Years later, the city would finally clear the waterfront and establish Waterfront Park. But the dream for Whiskey Row was never realized for Jones’ father, who died in 2003.

By 2004, the Jones siblings bought out a business partner to keep possession of the corner, spurred by their father’s vision.

“We did not want to see our father’s magic theater sold to somebody else. We’d all come to love this building, and we spent a lot of time in the building. … It was like family,” she said.

In 2008, her father’s dream advanced when Jones finally purchased the adjacent building, partnering with local developer Bill Weyland on the architecture and design. It would eventually become home to the 100,000-square-foot mixed-use venue known as Whiskey Row Lofts that opened a few years later.

Jones points to that project — coupled with the construction of the KFC Yum Center — as what lit the spark.

“It turned out to be good real estate, but the initial reasons were emotional. It was very emotional. It was, ‘Hell no, we are not selling Daddy’s theater and Daddy’s building,’ ” Jones said. “… Sometimes good real estate decisions are made from the heart. You have to be smart about it.

“But sometimes I think the heart can see what maybe the head can’t see, you know, the character and the beauty and the incredible architecture. And you just do it.”

In the 1960s, artists lived and worked along Whiskey Row, while live music and entertainment venues lined both Main Street on the south side of the block and Washington Street on the north in the 1970s and 1980s. The block started to wane in the 1990s and was nearly dormant by the 2000s.

Now, it is starting to resemble its old self again with restaurants like Doc Crow’s Southern Smokehouse & Raw Bar, Sidebar at Whiskey Row, Troll Pub, The Hall on Washington and Patrick O’Shea’s Downtown.

Hotel Distil and Moxy will bring a few more food options with Zombie Taco and Repeal, while national retailer Duluth Trading Co. became the anchor tenant of 111 Whiskey Row that also includes office space and a dozen apartments.

111 Whiskey Row was slowed by a large 2015 fire, which Jones called heartbreaking. The investors in that project lost much of the original masonry and heavy timber, but they started over again and eventually brought the building to life.

The fire proved to be just another obstacle as Jones has shown she’s too stubborn to give up — much like her father.

“I think he would be so happy to see that this vision was the right vision,” she said. “He was 20 years too early.”

The pioneer

While Valle Jones was working with Bill Weyland to bring her plans to life, Louisville restaurateur Tommy O’Shea and his business partners were stepping out on a limb to bring their pub experience to Whiskey Row.

I recently sat down with O’Shea in one of his restaurants as he reminisced about the history of his Whiskey Row investment. By the late 2000s, his family had multiple thriving businesses and a strong leadership staff, so they were in a position to take some risks. They set their sights on 123 W. Main St., the former home of CJ Schoch Heating Supply Co. Inc.

“They had not said the Yum Center was going to be there yet, but we knew that it was going to be one of three places,” he said. “There were three different areas of the city that they were thinking about.”

O’Shea bought the building for $600,000 in 2006 after the Yum Center was announced and started renovating the property with the goal to open the space up for a pub, prep kitchen and event space.

O’Shea and his business partners invested $4 million — financing $3 million of it — on the belief that the Yum Center’s presence would make it worth the money and hard work. O’Shea noted that he rarely took out loans but decided to tread new territory with this project.

“We may look smart, but we really weren’t smart,” he said of the decision, adding that “we’ve been blessed.”

O’Shea’s opened about a month before the Yum Center debuted, but the city had closed the sidewalks on Whiskey Row because the buildings were considered unsafe.

“For three, maybe four, years, we didn’t have a sidewalk,” he said.

That obviously hurt foot traffic, and he said the company’s other businesses had to carry the complex through the first few years.

Since 111 Whiskey Row and the Old Forester distillery have opened, he said, business is booming. During a big concert, he will pull workers from his Highlands and Jeffersonville, Ind., locations and open three of the four floors in the building for dinner parties. He said about 45 people will work the event for a three-hour window.

And when Poe Cos. and its investment partners open Distil and Moxy in November, O’Shea said, it should take Whiskey Row to the next level. He believes it could even create a Bourbon Street atmosphere like you find in New Orleans.

“I just think it’s going to be a great showpiece for Louisville,” O’Shea said. “The history there, it’s kind of unlimited (potential).”

A return home

Louisville-based distilling giant Brown-Forman Corp. officially returned home in June 2018 when Old Forester Distilling Co. opened at 119 W. Main St.

The $45 million distillery and visitors center retraces Brown-Forman’s steps at Whiskey Row, as it operated on the block from the 1880s through the early 20th century.

In the past year, more than 70,000 visitors have passed through the facility’s doors, and Old Forester’s leader said it is important to have a distillery as part of any Whiskey Row resurgence.

“The way I look at it is, if we didn’t do this, we would be negligent,” Old Forester President Campbell Brown told me. “This is a brand that means a lot to the city. As bourbon continues to grow in interest, broaden its wingspan and attract interest from outside of the U.S., you want to be able to expose and share these stories and processes with people that are [both] very familiar with how whiskey and bourbon is made, and those that may have no familiarity at all.”

Part of that experience is telling the story that the new distillery carefully weaves throughout the historic building, touching on the bourbon-making process and the evolution of the brand.

“The way I look at it is, if we didn’t do this, we would be negligent,” Old Forester President Campbell Brown said of the company’s Main Street distillery. “This is a brand that means a lot to the city.”

DAVID A. MANN

Brown said the project started coming into view years ago as Brown-Forman began looking at the Old Forester brand from a more strategic context, specifically how the “home place” concept that was used with other Brown-Forman brands could be applied to Old Forester.

The company’s history on the block and the collaborative investment of other local business leaders and developers ultimately swayed Brown-Forman executives.

“I think this quickly rose to the top in terms of where we wanted to make the capital investment,” Brown said. “And so we kind of bought these two buildings from the original investment group and started to do the work around securing it, figuring out what we could save, and then beginning to organize the thinking around how would you actually build an operating working distillery and home place that had a cooperage and warehouse and all the other components that you would need to make whiskey in an urban setting with absolutely zero wiggle room.”

He said figuring out how to stage construction and truck everything in from off-site areas in a way that was fast and decisive was a carefully orchestrated ballet.

The fire that wrecked 111 Whiskey Row in 2015 also hit Old Forester’s building, setting the project back 10 months. Thankfully, the company was able to save large portions of the building because much of it had been deconstructed and stored off-site. The main challenge was bracing the foundation and dealing with the erosion caused by all the water needed to extinguish the blaze.

“It took us a fair amount of time and some smart engineers to figure out how to make the location safe for us to continue the buildout,” he said.

Looking down from his office inside the distillery, he said Whiskey Row has helped position Louisville to take advantage of its unique position.

“We’re blessed, really, to have the kind of investment that we’re seeing in something that not many cities will ever be able to replicate,” Brown said of bourbon tourism. “It’s very much akin to what Sonoma and Napa [Calif.] have been able to do with the wine business. And now, I think it’s a competitive advantage for the city.”

An authentic experience

One of the final pieces in the Whiskey Row puzzle will be placed with the completion of the 12-story dual-branded Distil and Moxy hotels at the end of the block near First Street.

Hotel Distil is an upscale bourbon-themed concept that is part of Marriott’s Autograph Collection. It will have 205 rooms with 15,000 square feet of meeting space. The Moxy Hotel — an edgier Marriott brand that has gained a following in Europe — is connected to Distil and will have 110 rooms.

Steve Poe — whose Louisville-based Poe Cos. is developing the Moxy and Distil hotels in conjunction with Merrillville, Ind.-based White Lodging Services Corp. and Indianapolis-based REI Real Estate Services — said the project will fit in well on a street that will be fully open for business for the first time in several years.

“You’re sort of a renegade,” he said of the Moxy brand. “It’s sort of out-of-the-box.”

This will be Poe’s second and third hotels at First and Main Streets after he opened an Aloft Hotel fronting Whiskey Row a few years ago.

Poe started paying more attention to Whiskey Row once the Yum Center opened and distilleries started dotting both East and West Main streets.

“Main Street started becoming more of the ground zero area,” he said.

Poe gave the team leading the hotels credit for embracing what he calls an authentic local experience.

“You can talk about all these things, about building buildings, but it’s actually about the experience once they get here,” he said. “They have done a great job of incorporating the history of the block into the building, really into the DNA of the whole thing, into every part, from restaurants and food and beverage to the way you are greeted when you get there.”

Hotel Distil General Manager Dana Orlando said the Aloft will be marketed together with Distil and Moxy once all three hotels are active.

“So this is three unique experiences under one Whiskey Row hotel collection, and that’s something I’ve never been a part of before. I think that’s the exciting part of the revitalization is, there’s nothing like this in the city,” she said.

Speaking of marketing, Valle Jones said she has spoken with the other investors and developers on the block, and they are working on a collective marketing plan for Whiskey Row that could have national reach.

“Property owners see that their interests are aligned, and that we all care about this block and want to make it a destination,” she said. “It’s already a destination on some levels, but we want to double down on that.”